Moldova’s freezing temperatures and heavy snow have done little to dampen the election fervor.

Citizens will head to the polls on February 24 to elect a new Parliament in what promises to be a consequential competition. Moldova’s neighbors are certainly watching.

With approximately one million Moldovans living abroad in search of better wages, both Russia and the European Union have a stake in a stronger Moldovan economy. In addition, the United States has indicated strong support for Moldova to continue its path toward European integration and greater regional economic stability.

Alternating governments in Chisinau have wavered in their commitments to these objectives. Three weeks out, polling shows that the election will likely result in a change from the status quo, but the details are still unknown.

What we do know is that the election will answer three important questions for Moldova: Who do people trust to address corruption? Which parties will benefit most from the new mixed system of representation? And will Moldovans trust that their vote made an impact in a free and fair contest?

Who do people trust to address widespread corruption?

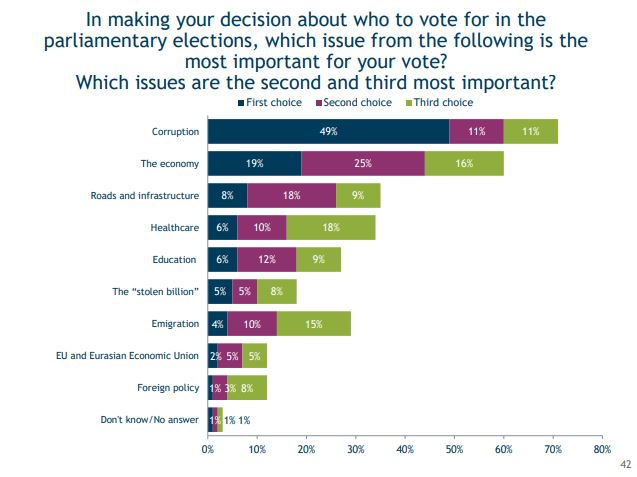

Voters have made it clear that corruption is the main issue driving their votes this election. Even the most casual observer of Moldovan politics knows that its citizens are very familiar with the debilitating effects of corruption found at every level of society.

At the personal level, almost one in four Moldovans have paid a bribe in the last 12 months, mostly to gain access to adequate healthcare. Locally, mayors are often perceived to be in the pocket of wealthy businesspeople. And at the highest levels, the lackluster response to the crisis of the “Stolen billion” that roiled the country in 2015—a crisis in which the equivalent of one billion dollars was literally siphoned away from three Moldovan banks, leaving citizens to foot the bill—left the economy even weaker than before and compounded citizens’ distrust of government.

Not surprisingly, the international community usually focuses on oligarchs and the judicial branch as the weak link in the fight against corruption.

Talk to a Moldovan on the street and they will tell you otherwise.

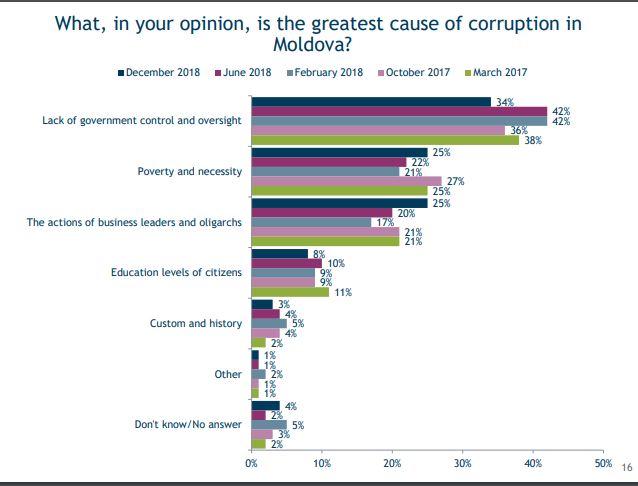

In a culture of pervasive corruption, Parliament has become the face of the problem. The International Republican Institute’s latest poll shows that citizens clearly believe that Parliament has the most influential role in enabling or combatting corruption. Citizens point to the lack of government control and oversight as the greatest cause of corruption, and Parliament consistently tops the list as the main culprit.

This amounts to a serious credibility problem for the current Parliament.

IRI has always encouraged parties to remain responsive to citizen priorities and build messages around voter concerns. Several political parties have seized on this public sentiment and made addressing corruption a central campaign promise. The results of this election will show who the public trusts to deliver on their promises.

Which parties will benefit from the new mixed system of representation?

This election will also be the first time that Moldovans have elected representatives under the new mixed electoral system.

Previously, all 101 seats in the Parliament were allotted to parties based on the proportion of the nationwide vote that each party received. Forty percent of the vote would give a party 40 seats. This enabled some parties to ignore sparsely populated regions and remain competitive with essentially only urban votes. Under the new system, Moldova and its diaspora population have been divided into 51 districts, each with a single seat in Parliament, while the remaining 50 seats are allotted with the old proportional system.

While the new system has been controversial, it has opened the possibility for more directly representative government. Parties that want to be genuinely competitive in the election will need to appeal to voters in every region, not just the high-density urban areas of Chisinau, Balti and Orhei.

This means crafting a common message that resonates with all Moldovans. But it also means addressing local issues and building lasting relationships with citizens in the regions.

IRI has organized “listening tours” over the last year to help parties build out their regional presence and reach voters outside of Chisinau. During a listening tour, party leaders road-trip across Moldova and make stops to talk with their regional representatives about the issues important to their communities. IRI spoke with one woman who expressed that her party’s regional branch would benefit from focusing on local issues. “We do not know how to explain and show to our voters that the party is working and can actually solve our problems,” she said.

It is likely that parties seen as out-of-touch with local issues will do poorly at the polls this February. So, this election will reveal which parties are in the best position to appeal to all of Moldova’s diverse groups of voters.

Will Moldovan citizens be satisfied that the election was free and fair?

IRI believes that an election consists of more than just Election Day. A vital aspect of any election is the public’s perception of the integrity of the electoral process, from campaigning through the validation of the results. Suspicions of foul play or fraud weaken the ability of newly-elected leaders to focus on the hard process of governing. Public approval and buy-in is important for any government, and nobody benefits from contested election results.

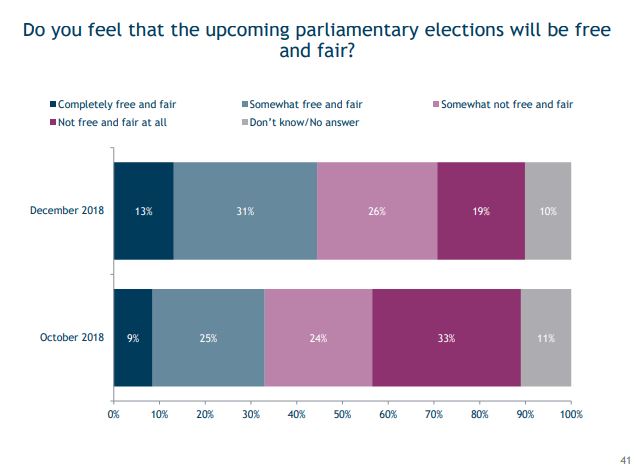

Currently, 44 percent of Moldovans believe that the upcoming parliamentary elections will be free and fair. That is an unfortunately low percentage for such a consequential election.

This low voter confidence may be a lingering effect of the Chisinau mayoral election in June. After a Moldovan court invalidated the results because of an Election Day get-out-the-vote appeal, thousands took to the streets to protest what they saw as a rigged system.

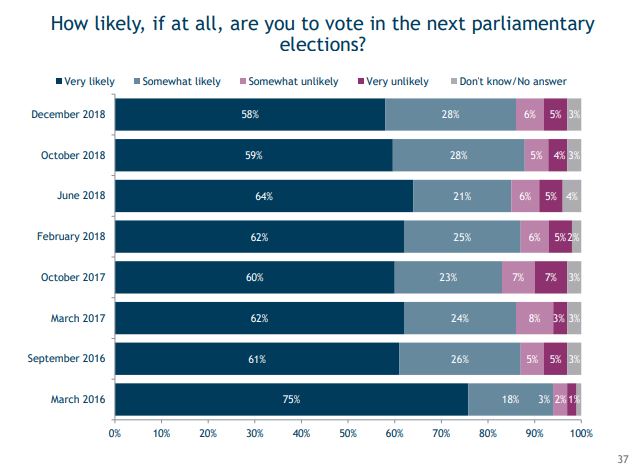

Importantly, this concern about the integrity of the electoral process will not be keeping people from the polls—86 percent of Moldovans intend to vote in the elections.

IRI is already on the ground with a team of observers and analysts watching the election proceedings. Observers are meeting with candidates, mayors, election officials, members of the media and other key players in the election process to build confidence in the integrity of the election and report fraud where it exists. Their findings are being shared on online platforms and in the Moldovan press for all citizens to see.

While election observers are a vital piece of a free and fair election, the public’s perceptions—informed by observers—are what ultimately matter for the health of Moldova’s democracy. If handled correctly, this election could be a positive step towards rebuilding the public’s trust in the democratic process and creating a more stable democratic neighbor for Europe and the greater Eurasian region.

That can be considered a win for Moldova, regardless of which parties come out on top.

Top