Ghosts from the Past: How Northern Ireland’s Democratic Woes Complicate a Brexit Deal

Three – The number of weeks until the United Kingdom departs from the European Union whether a trade deal is in place or not.

391 to 242 – The vote count by which the British Parliament rejected Prime Minister Theresa May’s Brexit proposal on March 12 after an even larger margin rejected an earlier proposal January 15.

On June 23, 2016, citizens of the United Kingdom (UK) passed a referendum to leave the European Union (EU), a move now commonly referred to as “Brexit.” Since then, the UK and EU have sought to negotiate withdrawal terms and had until March 29, 2019 to do so. However, both parties have failed to agree on a post-Brexit relationship, and if the UK and the EU fail to agree on a plan the British Parliament will ratify, or if no delay is agreed upon, the UK will exit the EU on March 29 with no trade deal. A no-deal exit poses a major risk of economic disruption for the EU and would likely be catastrophic for the UK. In our interconnected global economy, an economic recession in the UK could have ripple effects reaching the U.S.

The primary sticking point is the border between the Republic of Ireland, an independent country within the EU, and Northern Ireland, which remains part of the UK. The UK’s departure from the EU’s customs union would likely require the establishment of a hard border to regulate trade coming into and out of Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK. However, both sides want to avoid a hard border between Northern Ireland and Ireland.

Until a solution is found, the EU proposes to keep the UK in their customs union and Northern Ireland aligned with several trade rules of the EU’s single market. This solution is commonly known as “the backstop”. But both members of May’s Conservative party and Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionist Party, whose support the Conservatives rely on, have reservations. Some Conservative Party members fear indefinite membership in the customs union and Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionist Party fears de facto separation from the rest of the UK. So why not just establish the hard border and conclude a Brexit deal? Let’s consider a final number:

3,532 – The number of people killed from 1969-2001 during the Troubles of Northern Ireland.

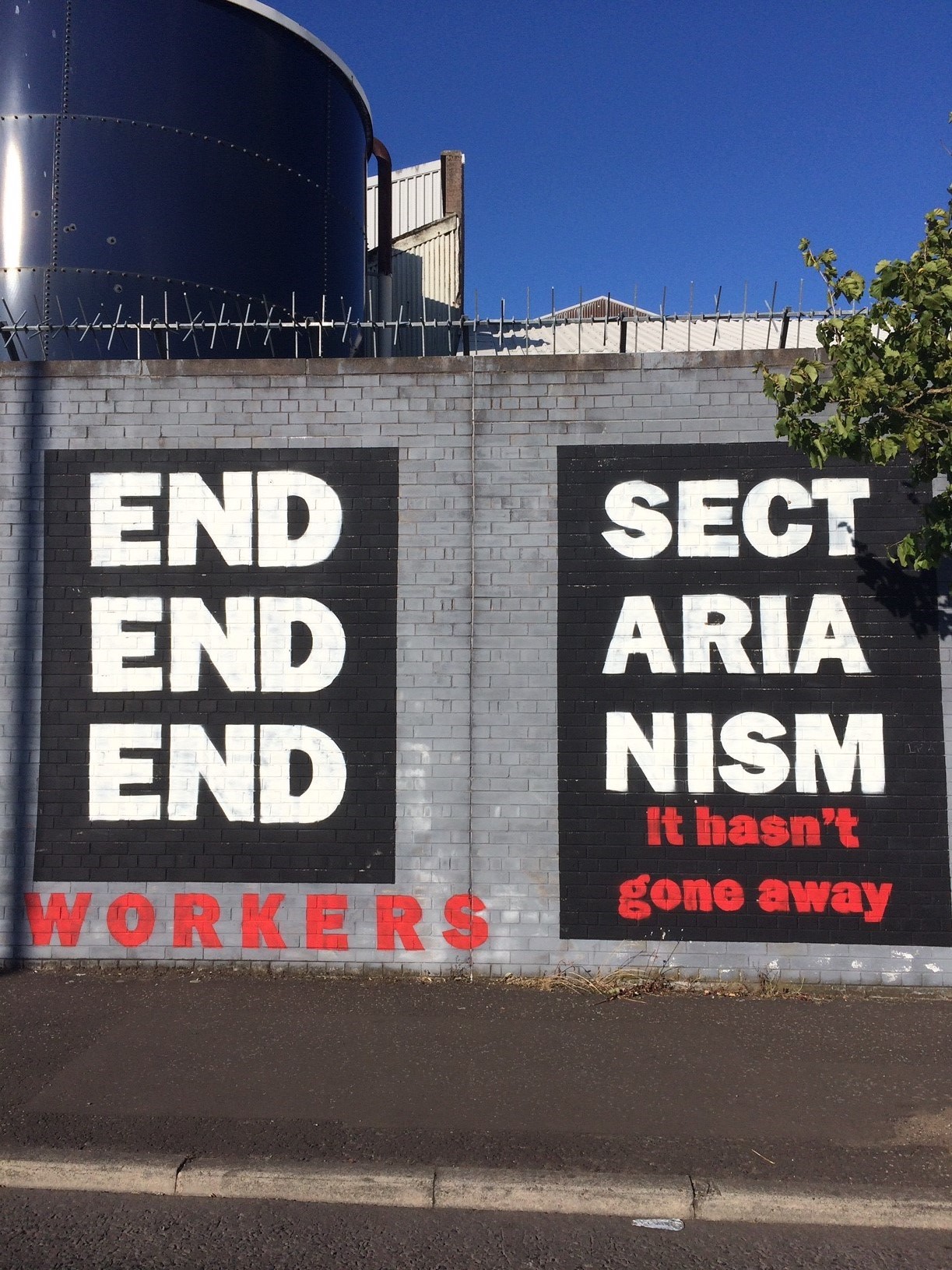

Both sides fear the establishment of a hard border could reignite violent conflict between Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland which constituted the Troubles. Northern Ireland’s Catholic population has historically pushed for unification with Ireland, while the Protestant population has resisted such a move.

As I witnessed during a study abroad course in Northern Ireland last summer, passing from Northern Ireland to Ireland is currently a seamless transition, almost unnoticeable. In the literal sense, a hard border would restrict the flow of goods and people between the Republic and Northern Ireland. More important though is the symbolism a border would impose. The current nearly-invisible border reduces the mental and emotional separation Catholic Northern Irelanders feel from the Republic.

Fear of a return to violent conflict isn’t unwarranted. Northern Ireland is in a state of fragile peace, where conflict is absent but could be easily provoked. During my time there, a few Protestant groups were setting large bonfires and planning marches to commemorate the victory of William of Orange over the Catholic King James II at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. This period is known to raise inter-communal tensions and localized violence was reported during one of my nights there.

More recently, police blamed a group known as the New Irish Republican Army (IRA) for a car bomb in Derry, a town close to the Irish border. Noting the IRA’s attacks on British border checkpoints during the Troubles, the re-establishment of hard border checkpoints could provoke an attack, which might spark further violence.

This current state of fragile peace is a product of a long history of democratic exclusion and poor governance. The UK first partitioned the island of Ireland in 1920, carving out the northeastern end of the island as Northern Ireland. The next 50 years were largely characterized by exclusion of Catholics from political decision-making through different mechanisms of democratic manipulation that minimized the number of Catholics who could vote and the importance of their vote.

Reminiscent of, and indeed inspired by, the civil rights movement in the U.S. at the time, Catholics and some fellow Protestants began protesting for equal access to housing, jobs and the democratic process in the late 1960s. Poor political leadership in Northern Ireland that portrayed the civil rights movement as an IRA front is at least partly to blame for the wide-scale violence which ensued in Northern Ireland. Violent suppression of the civil rights movement led to a self-fulfilling prophecy by which the IRA reemerged.

Since the Troubles concluded with the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, Northern Ireland has struggled to achieve prosperity and stability. Signs of hopelessness in Northern Ireland are found in the country’s drug abuse and suicide rates. The number of deaths caused by prescription drug abuse consistently rose from 2006 to 2016 and is now considered an epidemic. Meanwhile, the number of suicide deaths since the Good Friday Agreement has eclipsed the total killed during the Troubles.

At the helm of Northern Ireland’s problems is a dysfunctional government, or since January 2017, no government. The government at Stormont collapsed with the resignation of Deputy First Minister Martin McGuinness of the nationalist Sinn Fein party following allegations of corruption against First Minister Arlene Foster of the unionist Democratic Unionist Party (DUP). The Good Friday Agreement requires the largest nationalist and unionist parties to both participate in the parliamentary executive. While this system of government does prevent the domination of one ethnicity or ideology in political decision-making, it has the unintended consequence of reinforcing pre-existing divisions, as neither party has to garner votes from the other side. Its rigidity also leads to the kind of government collapses Northern Ireland is currently experiencing. Based on conversations with the civil society groups my class met with, peace in Northern Ireland seems to be persisting in spite of its government rather than because of its government.

The case of Northern Ireland and the Brexit backstop demonstrates the international ramifications localized conflicts can have, even decades later. While faced with challenging circumstances of inter-ethnic tension and anti-colonial sentiment, the Troubles was not a forgone conclusion with the partition of Ireland in 1920. Rather, political manipulation of the democratic system is at least partly to blame for the Troubles.

Since their conclusion in 1998, nationalist and unionist political leaders have played to their bases rather than lead a process of reconciliation. This has left a state of such uncertainty and fragility that the entire process of Brexit could be derailed by the six counties of Northern Ireland. Proper democratic governance matters not only for the people of today, but also for the international relations of tomorrow.

Top